I have always wanted to write about the war, to tell stories set in the backdrop of the war but always considered myself inept. No matter the many books and articles I read or the documentaries I watched on Biafra, I just still felt that there was a lot more to learn and know before I could voice an opinion on it publicly. What did I want to say that had not been said? And what was the urgency and utility of my stories on the war?

My very first knowledge of the war were from the accounts my father shared with me. His personal stories about living through the war as a young boy not older than eleven. And his stories were focused on how they survived the war.. How they hunted and ate lizards because beef and crayfish had become scarce and too expensive; lizards being the only readily available source for protein, lest they become malnourished and suffer kwashiorkor. How when the war drew nearer to their hometown in Mbaise, they fled and walked kilometres to a neighbouring town and found refuge in a cave where they lived for weeks until the war ended.

His tellings of the war were never a chronicle of the events of the war. His tellings were always detailed and punctuated by the mundanities of those days. He recalls even the jokes he shared with his siblings on those mornings they hawked pepper. And tells me of times when they drifted from their mission to play football with other kids in the community.

While not a story set in the late ‘60s world of Biafra, I think i came close to actualising my dream making A Quiet Monday. It provided me an avenue to express my feelings about Biafra and what it still means for Igbo people today. Looking back now, i am thankful for the stories my father shared of the war because it made me see that every story can be affected by nuance. That even in bleak and desperate circumstances people will seek joy. That people will tell jokes and laugh and kick footballs on the streets. And it didn’t make their circumstances any less tragic.

Thus, I made it goal to ensure that the characters of A Quiet Monday stayed human and didn’t become things whose sum of being can be easily defined by the tragic events surrounding their lives. Some of the validating reviews of A Quiet Monday is that it is bereft of the kind of mawkishness people have come to associate with stories of sad events and people who live through them.

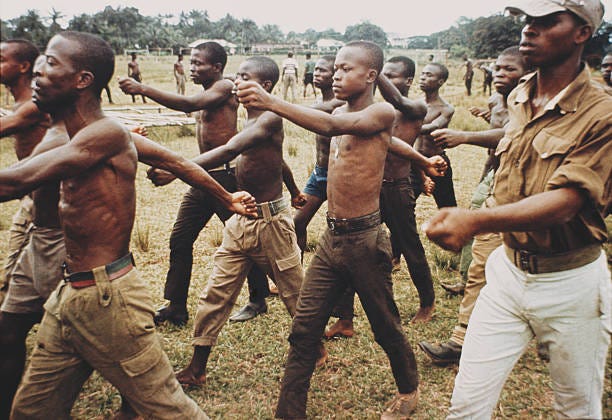

Every 30th May is Biafra Remembrance Day. It is baffling that it’s not a national event but if left to the government of Nigeria, Biafra would be hidden, completely forgotten. Igbo people who care enough about history, commemorate that day not only to remember those who lost their lives in the fight for Igbo sovereignty but to celebrate our survival too. Some who are social media savvy tweet hashtag Ozoemena and share stories and documentary clips of the war on our Instagram and Facebook accounts. On many pages you will find photos of young children, many of them not older than 6, with limbs so thin you wonder how they are able to carry their protruding stomachs and heavy heads. Many news articles of the war simply describe them as “Biafra Babies” as though suffering kwashiorkor was a prerequisite to being a Biafran baby.

A particular Twitter account that specializes in sharing Igbo history shares photos and videos of those kids every 30th May that it started to read me the wrong way. It’s the kind of depiction often propagated by pro-Biafra separatists whose every story of the war serves to remind Igbo people of the atrocities of the federal government of Nigeria in order to propel their secessionist ambitions. However, I worry about how that kind of telling places those children and in extension every Igbo person who lived through the war as victims. Permanently.

I think we need to engage with the stories of the war better. Every time I read about the war or learn something new I am marveled by the resilience of my people and it fills me with chauvinistic pride. There were deliberate actions by the federal government of Nigeria to completely wipe out Igbo people and yet we survived. I think we do not celebrate this survival enough. Nor appreciate enough our ancestors who fought this war and for whom without their bravery, strength and courage, we would not be here today. Our heroes.

and this isn’t an attempt to deny or ignore the validity of conversations about the hurt from the war or the unconscionable atrocities committed by the federal government of Nigeria. Those conversations matter . But I’m also aware of how we are shaped by the stories we are told and how they are told. And I am interested now in how future generations of Igbo people engage with Biafra.

We lost too many people to the war. The numbers are in the millions. But as a people, we survived. That should matter more. And thus, should make more concerted efforts towards surviving Nigeria despite whatever may be thrown at us as a people.

Because I grew up outside Igboland, I experienced ethnic bigotry early. A popular sentiment still held today was that Igbo people were not to be trusted with the leadership of the country, that they spelt doom for the unity and progress of Nigeria. And so, I’ve always lived in this country with an awareness that we, the Igbo, are not fully welcomed. That by merely existing we are considered threats.

However, the secessionist ambitions pervading the southeast today has done us more harm than good and has further divided Igbo people and I find it to be antithetical to the idea of Biafra. Biafra stood for Igbo unity and sovereignty. We’ve left a few, a minority amongst us, trample on us. how does a group of people who swear that they have Igbo people at heart become threats to their fellow Igbo people. Sometimes I feel like I have been living through a fever dream year after year experiencing the Monday sit-at-home in the southeast.

Today is January 15 and happens to be a Monday too. 54 years ago our people celebrated an end to war. And began to rebuild their lives and make up for the losses of the years of the war. Human and material losses. We are still rebuilding till today and cannot afford to tear ourselves down. We must consider how much we stand to lose if a war breaks out again and the setback that will mean for us and realign with one another for our collective good.

Our parents and grandparents who saw this war prayed Ozoemena (may it not happen again). May every Igbo person continue to honour this prayer. May we always remember our heroes and honour their sacrifice. May we always remember. Ozoemena.

Igbo ga-adi.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on this. May this evil not happen again. 🙏