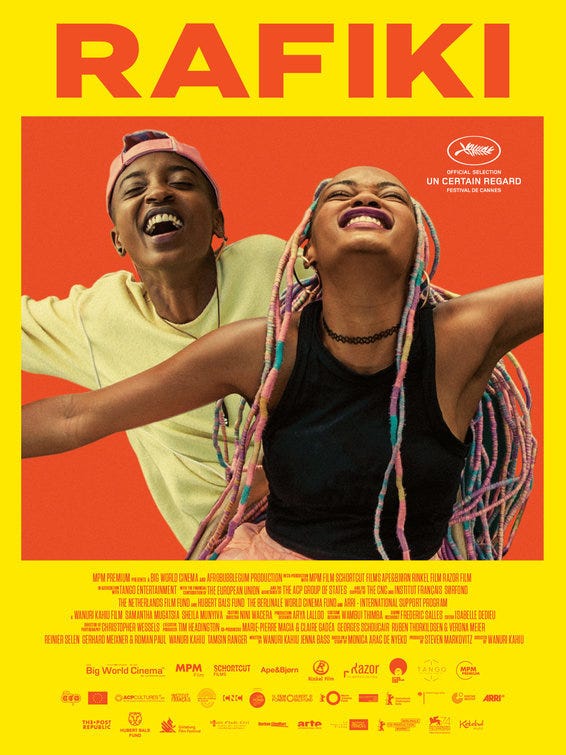

Rafiki: A portrait of what it means to be in love and lesbian in Kenya

The first public screening of Rafiki was at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, becoming the first Kenyan film to screen at the festival. It would also go on to screen at other reputable film festivals such as the Toronto International Film Festival and Black Star Film Festival later that year. But no matter the critical acclaim and international recognition this film garnered, the Kenyan Film Classification Board (KFCB), the country's censors board, banned it from showing in Kenyan cinemas due to its homosexuality theme.

Kenya is one of the many African Countries where same-sex relationship is prohibited. Under the Kenyan constitution, it's punishable for up to 14 years in prison. However, Kenya just like any other African country does not need the legality of the law to back its homophobia. And this is what director Wanuri Kahui brilliantly captures in this film. In portraying the valid experiences of queer people in Kenya, Wanuri shows us how queer people are bullied: from the podium of churches to the roads of the street, gay people are persecuted and told that they're an aberration, a taboo, despised by God and men.

And through the character Kena (Samantha Mugatsia) we learn the frustrations of being queer even while still in the closet: enduring the harsh jokes and taunts at queer people that are thus inadvertently directed at you. Living through homophobia would then mean dealing with shame and anxiety. The first time Kena and Ziki (Sheila Munyiva) are alone and about to be intimate, Kena refrains from kissing Ziki, what her face, her averted eyes, reveals in that hesitancy isn't the nervousness that comes with new love, but shame. Shame in affection.

When Kena overcomes this shame and is finally intimate with Ziki, Ziki would despair "I wish this were real" underscoring the lived experiences of many queer Africans who are often averse to seeking and nurturing relationships because of the seeming futility of it in a homophobic Africa. Kena and Ziki are subjected to verbal and physical abuse the day they're found loved up in their safe space—an abandoned rusty bus in an isolated area of their community. They're mobbed, beaten, slapped, cursed, and jailed. What would follow is Ziki surrendering to the oppression and giving up on the relationship despite Kena's pleas that they'd weather the storm. "Are you going to marry me?" Ziki demands of Kena. The end goal of a romantic relationship shouldn't always be marriage, but in the African society of our lesbian protagonists, it is, and even an aspiration for young girls. Ziki hates this, though, and aspires to be everything but it. In her words, she does not want to be the "typical Kenyan girl". But the talk of marriage here becomes symbolic of a "happy ending" that is denied gay people.

"I wish we could go somewhere where we'd be real," Kena herself would think out loud in a scene where Ziki isn't even present as though a response to Ziki's earlier "I wish this were real." Sadly, this "real place" for a lot of the African queer is the western world. Many gay Africans seek asylum yearly in countries such as the UK, Us, Canada, etc. And even though living in these countries does not mean that they have fled from homophobia completely, it is a breath of fresh air to live in a place where your existence isn't defined as illegal at least, where there are possibilities of a "happy ending" within or outside the confines of the institution of matrimony. Kahui looks to the future of queer Africans with hopes such as this. The film's ending is an uplifting one as Kena and Ziki are reunited after many years.

But even within the bubbly world of film and its many possibilities, the KFCB had asked that Wanuri stripped Rafiki of this positivity as it preached for homosexuality against the country laws, a further attempt to marginalize gay Africans.

Queer Kenyans and their allies continue to push for a reform of their country's aged long homophobic laws. Activists have pushed for a repeal of sections of the constitution criminalizing homosexuality. And although the High court on May 24, 2019, failed to decriminalize homosexuality, the activists haven't relented in their fight. In fact, the earlier High court's ruling in favour of temporarily lifting the ban on Rafiki so the film could be screened in cinemas and be eligible to be submitted for the 91st Academy Awards under the Best International Feature Film section, created a favorable precedent for the pursuit of decriminalizing the homophobic laws.

https://youtu.be/GGAWuMuumDQ

Wanuri Kahui herself is unrelenting in her desire to see that the ban on Rafiki is lifted permanently, despite the recent April 2020 court ruling that upheld the ban. Speaking to the Thomson Reuters Foundation on the court's ruling, she said: "We are disappointed, of course. But I strongly believe in the constitution and we are not going to give up."

Rafiki is available on Showmax SA, Amazon Prime, Hulu, and BFI Player.